Situatie

Solutie

In a nutshell, UBI is a small Rust program that installs binaries from GitHub or GitLab. Software developers don’t just publish their code on these platforms; they often build and publish it there too. UBI goes directly to the source while automating the boring parts for you.

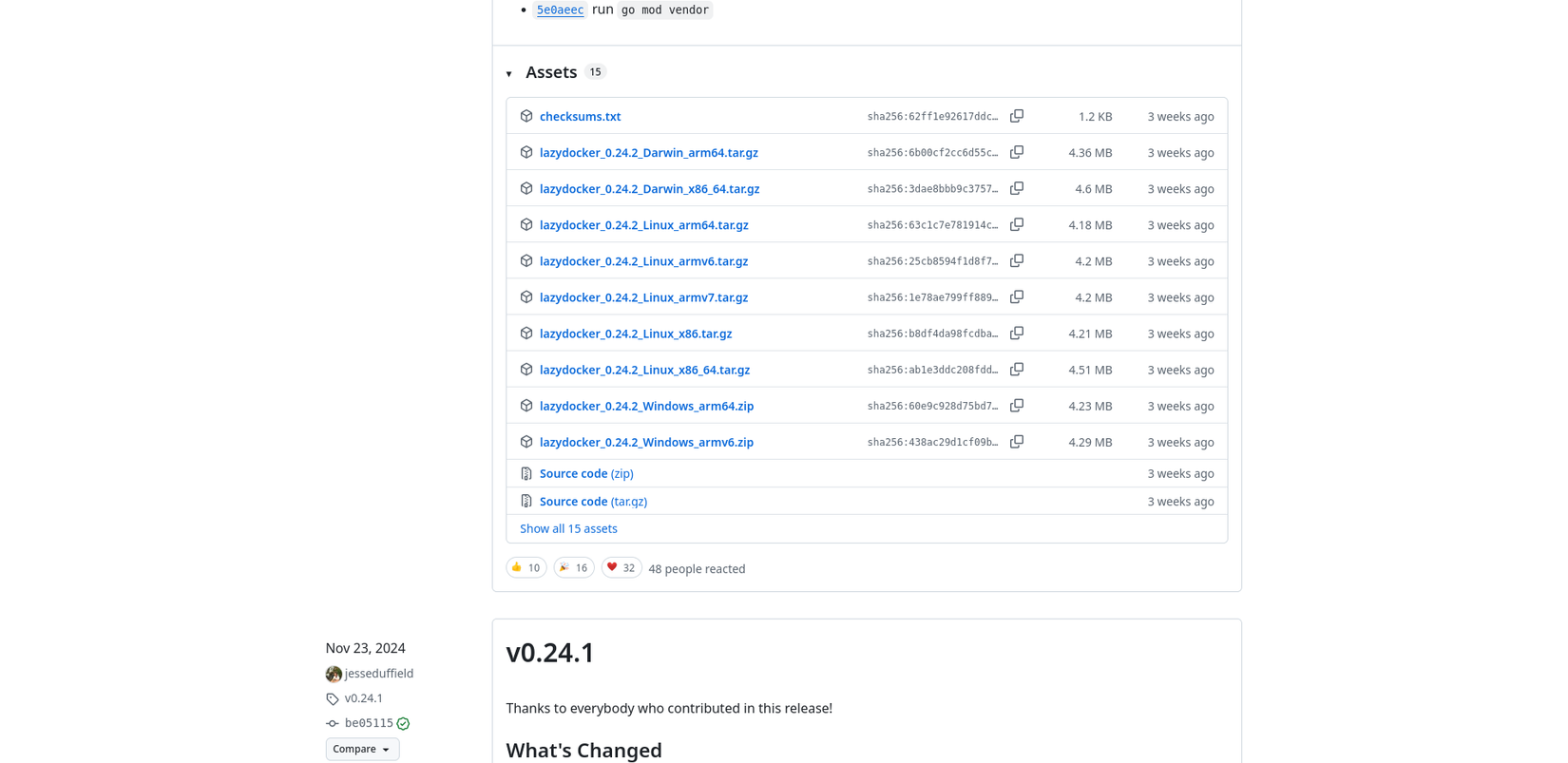

A GitHub release is a set of project artifacts (build outputs, like tarballs) published to a project-specific web page on GitHub. For example, the lazydocker repository publishes binaries you can download and execute. The GitHub releases page for a project may have many links, organized by version.

The filenames typically contain many details about the build artifact. For example, you can see from the previous image that lazydocker’s filenames look something like this:

lazydocker_0.24.2_Linux_x86_64.tar.gz

Libc is the C standard library. It’s a collection of shared objects (e.g., libc.so.6 or libresolve.so.2) on most Linux systems that provides programming utilities for applications. They’re crucial for applications to function.

The problem UBI solves

For a one-off trial, manually downloading software is fine. But for long-term usage, it becomes a chore—you must visit the page, download and unpack the archive, move the binary, set the execute bit, and then change its ownership. You may write a Bash script to simplify that process, but it’s too much friction just to install one application.

UBI makes the installation of any software from GitHub or GitLab convenient. Now small and independent projects are more accessible than ever. It means you can step outside your distro’s ecosystem and access bleeding-edge software from one of the largest repositories on Earth.

How UBI finds the right binary

GitHub releases contain build artifacts for various platforms, versions, and supporting documents. UBI must choose the most suitable one for your system. UBI uses a process of elimination to exclude irrelevant archives, which looks like this:

- Filter out unknown extensions (e.g., .foo, .bar).

-

-

- Operating systems.

- CPU architectures

- Libc builds (e.g., musl or glibc).If there’s one archive left, use it; otherwise, filter out irrelevant…

-

- Filter out 64/32 bit

One archive should remain; otherwise, you can explicitly specify a match using the –matching flag.Once it has selected the archive, UBI must choose the correct executable from it, because often these builds come with additional files.

The process is simple; it will select a file whose name either…

- Matches the project.

- Starts with the project name: e.g., foo-v1.2.3, foo-linux-amd64.

Installing UBI

Installing UBI is straightforward, although some would groan about curl-bashing. I’ve improved the installation script so that it includes the necessary “BIN_DIR” in your PATH variable. That is where your installed binaries live, and you’re free to change it, but if you do, you must use the –in flag when installing applications. I recommend creating an alias for that.

You must read and verify scripts before executing them like this (aka curl-bashing). Please verify the installation script for UBI.

BIN_DIR="$HOME/bin"

mkdir -p "$BIN_DIR" \

&& curl --silent --location \

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/houseabsolute/ubi/master/bootstrap/bootstrap-ubi.sh \

| TARGET="$BIN_DIR" sh \

&& { \

if [[ ":$PATH:" != *":$BIN_DIR:"* ]]; then \

for rc in ~/.zshrc ~/.bashrc; do \

if [ -f "$rc" ]; then \

echo "export PATH=\"$BIN_DIR:\$PATH\"" >> "$rc"; \

echo "Added $BIN_DIR to PATH in $rc"; \

fi; \

done; \

fi; \

}You may need to reload your shell if it added the path to your config: source ~/.bashrc for Bash or source ~/.zshrc for Zsh.

Using UBI

To install software from a GitHub repository, all you need are the owner and repository names. A GitHub URL looks like this:

https://github.com/houseabsolute/ubiThe path segments “houseabsolute” and “ubi” are the owner and repository names, respectively.

Just as an example, to install UBI (with UBI), execute:

ubi --project houseabsolute/ubiThat’s it. In your shell config, you can create an alias or function to make things easier:

add() {

case "$1" in

ubi) ubi --project houseabsolute/ubi ;;

*) echo "Unhandled project: '$1'" ;;

esac

}“install” is a command on most systems, so I called the function “add” instead.

Handle edge cases

Sometimes the match algorithm doesn’t resolve to a single archive, because the publishers defined some additional (unhandled) elements in their names. You have a few options for managing these edge cases.

Given a release that has additional “foo” and “bar” elements in its name:

ubi-Linux-musl-foo-x86_64.tar.gz

ubi-Linux-musl-bar-x86_64.tar.gzThe “–matching” flag allows you to distinguish between them:

ubi --project houseabsolute/ubi --matching fooOr you can use Regex:

ubi --project houseabsolute/ubi --matching-regex '.+-foo-.+'To install a specific version, specify a tag:

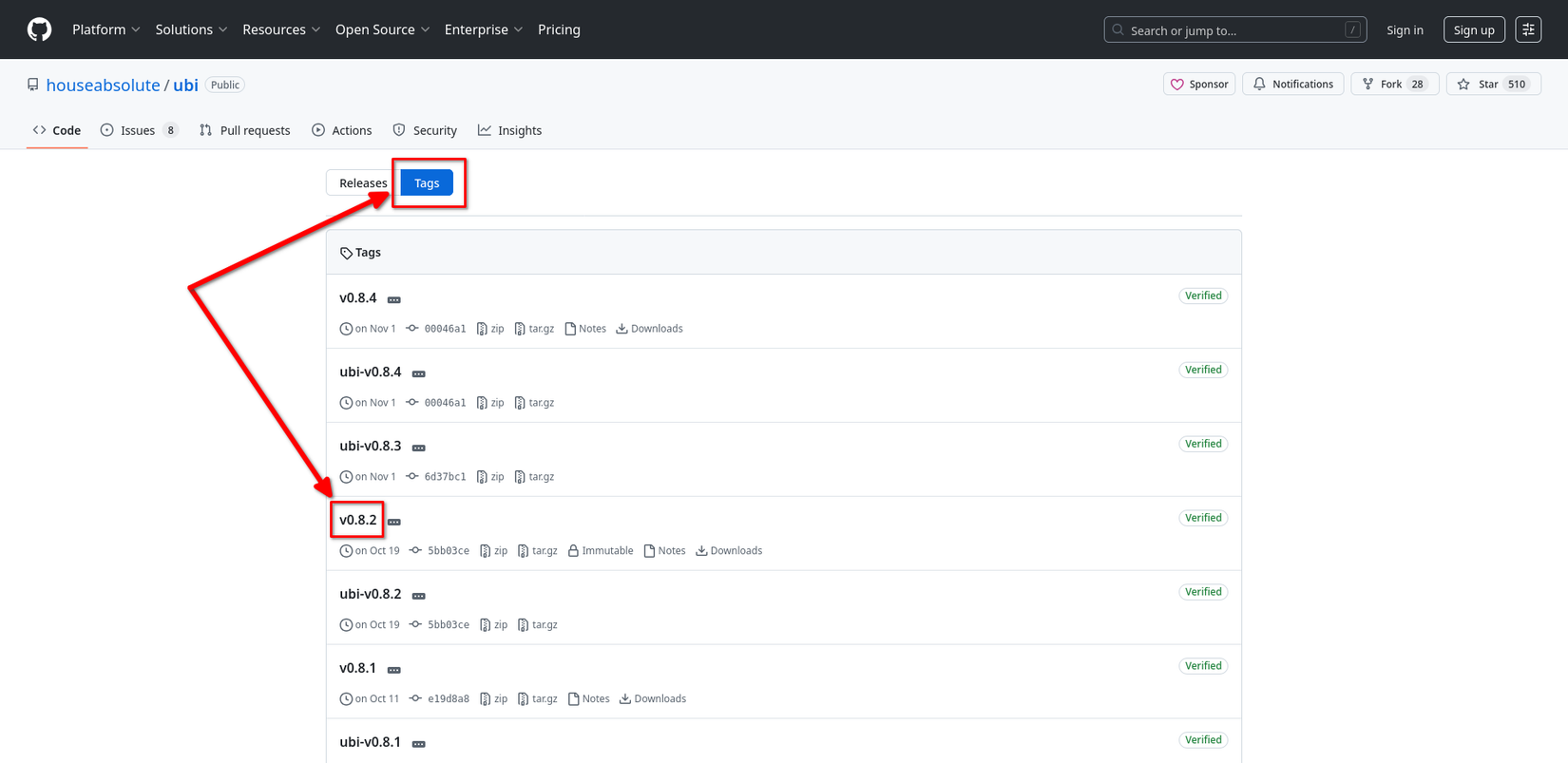

ubi --project houseabsolute/ubi --tag v0.8.2The image shows how to determine tag names for specific releases. Sometimes the archive doesn’t contain a suitably named executable (e.g., the project name). In that case, use the “–exe” flag to specify the target:

ubi --project houseabsolute/ubi --exe ubiLastly, you can specify the output directory for the binary with the “–in” flag:

ubi --project houseabsolute/ubi --in ~/.local/binUBI is a simple program that plugs a long-standing gap in the Linux software ecosystem, where niche or independent packages were difficult to get automatically. UBI fills that void, and it won’t make a fuss. It doesn’t pull in thousands of dependencies or require SELinux sandboxing. There’s no caching or complex packaging formats. It leverages a channel that most developers already use, giving you access to bleeding-edge projects.

I also use Distrobox to install hard-to-get software on any system. With Distrobox, UBI, and the official and community Linux repositories: it’s difficult to find applications I can’t use.

Leave A Comment?