Situatie

Backup

AROS stands for “AROS Research Operating System.” The name may be a recursive acronym, but it’s an attempt to recreate the famed Amiga operating system, AmigaOS. AROS aims for broad compatibility with AmigaOS, but it’s a complete reimplementation. One advantage it has over AmigaOS is that it runs on different types of computers, including regular PCs.

As with Linux, there are several versions of AROS available. One of them is AROS One. Other versions include Icaros, AROS Vision, and AspireOS.

4 ReactOS

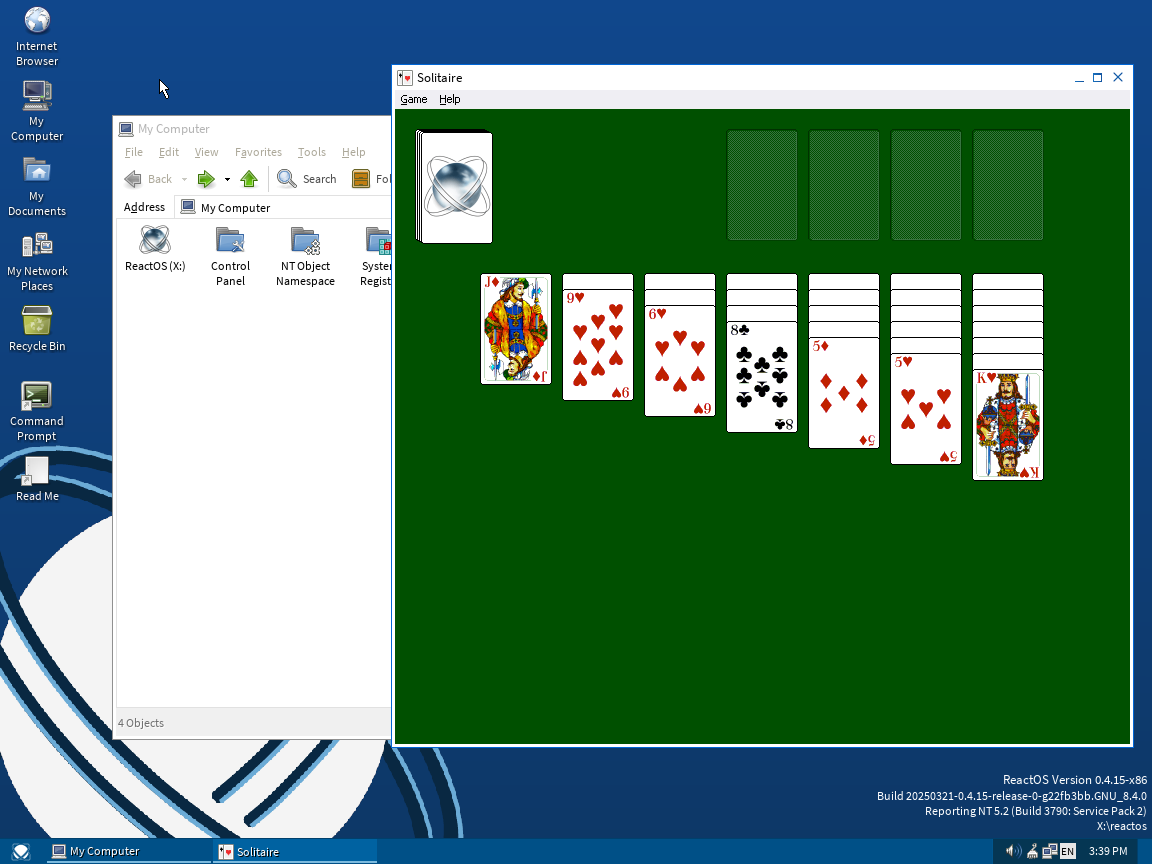

If AROS is dedicated to reinventing AmigaOS, ReactOS tries to reimplement Windows in an open-source fashion. It also tries to mimic the classic Windows 9.x look-and-feel. Under the hood, it’s implementing the Windows NT strain, so it aims for compatibility with modern Windows versions.

In practice, development is slowed by the need for reverse clean room engineering to stave off lawsuits from Microsoft. Microsoft’s APIs are also a moving target, so developers often find themselves having to start from scratch.

Still, you can download and run images of ReactOS. I found it to be quite usable. It even includes a Solitaire game, which is something that has been omitted from more recent Windows versions, at least in an ad-free version.

3 FreeDOS

While ReactOS aims to recreate Windows NT, see if you can guess what FreeDOS is trying to reimplement. FreeDOS is an obvious clone of MS-DOS. The single-tasking, single-user MS-DOS. The DOS with the 640k barrier, unless you run a memory manager (which it does include).

Why would you want to run such an operating system in 2025? The most obvious reason is nostalgia. I grew up on MS-DOS, so it’s a fun trip down memory lane. You can run old business software and, more importantly, games on modern or even vintage PC hardware if you don’t mind scrounging for new CMOS batteries. One practical use for me was reflashing the BIOS on a Linux-only netbook. Many BIOS utilities only work with DOS. You could also use it as a platform for embedded systems due to its simplicity compared to even minimal Linux distros.

2 GNU Hurd

Before the Linux kernel existed, Hurd was the GNU Project’s first attempt to build a kernel for a free software operating system that gave anyone the ability to read and change the source code. Based on Carnegie Mellon University’s famed Mach kernel, Hurd is another attempt to build a microkernel-based kernel.

Unfortunately, the development of the kernel has been much slower than the developers originally intended. The Linux kernel leapfrogged Hurd, but it’s still an active project. Debian has made images of a Debian/Hurd distribution available, but it’s not yet stable for production work. The biggest hurdle appears to be the shortage of drivers, as most of the energy has shifted to Linux. I’ve only managed to make it to the installation screen in a VirtualBox VM. If you want to tinker with an OS in a virtual or spare machine, Hurd might be worth a look if you can get it to work.

1 The BSDs

Of the non-Linux open source OSes, the most prominent might be the BSDs. The BSDs collectively can trace their heritage to the Berkeley Software Distribution, created at UC Berkeley starting in the late 1970s. They modified the original Unix in ways that appealed to other universities. BSD was also popular on workstations because it was among the first major OSes to implement TCP/IP. This made it easy for these workstations to be networked and laid the groundwork for the modern internet.

Of the BSDs, FreeBSD is perhaps the best-known. It grew out of the 386BSD project to port BSD to PC-based hardware. When that project ground to a halt, a number of developers used the source code to create their own version. FreeBSD aimed to continue 386BSD’s attempt to primarily focus on PC and Intel hardware at the expense of other architectures. These days, FreeBSD runs on a variety of architectures. It’s best known for its file server abilities, with native support for ZFS. FreeBSD powers Netflix’s Open Connect content delivery network as well as the FlightAware flight tracking site.

NetBSD is another offshoot of the 386BSD project. Where FreeBSD initially focused on x86 computers, NetBSD aimed for portability, creating versions for nearly any computer architecture in existence. Want to run it on your PC? Sure, you can do that. Do you have some old machines, maybe even a Motorola 68000-based machine like an old Mac or Amiga? You can run NetBSD on that, too.

Maybe you even have a Digital Equipment Corporation VAX minicomputer? Yes, you can get NetBSD for that, too. NetBSD’s slogan is “Of Course It Runs NetBSD.” It’s even run on a toaster, as seen on Laughing Squid.

OpenBSD is the result of a dispute that NetBSD developer Theo de Raadt had with other members of the project. He split off and started his own system. OpenBSD is renowned for its focus on security. They claim to have only had a few remote holes in the system throughout its development. This is an impressive claim for any system, even an open-source one. Parts of OpenBSD have become popular in other places, like OpenSSH and the tmux terminal multiplexer.

DragonFlyBSD is a system that has made some radical changes to the standard BSD codebase. The system features the HAMMER2 filesystem with deduplication and snapshots for reliability. It also offers virtual kernels, where a kernel can run in user space rather than in the usual privileged mode. This makes it easier for developers to debug kernels.